MacGuffin talks about objects in motion

We sat down with MacGuffin, co-curators of Migration – the Journey of Objects, and asked them five quick questions about their work on the exhibition.

We sat down with MacGuffin, co-curators of Migration – the Journey of Objects, and asked them five quick questions about their work on the exhibition.

We were mainly inspired ‒ or rather: uninspired ‒ by the congested design world in which we worked when we started. We felt it was pretty much obsessed by commercial success, star designers, an overload of new chairs and an obsession with ‘innovation’. We were much more triggered by the ‘afterlife’ of everyday objects. How are they used? What does the world look like when you observe it through the lens of an object? In a way, we wanted to stretch the definition of design. Our second inspiration was Hitchcock, one of the greatest storytellers ever. He invented the word ‘MacGuffin’, the object in a movie that sets the story in motion. We borrowed the name because we wanted to create a platform that is not so much about the design of objects, but rather about the stories they generate.

We are living in a world in which migration is a constant, and the traditional distinction between ‘native’ and ‘immigrant’ is of diminishing relevance. Individuals migrate, and so do cultures, skills, religions, ideas, objects and materials. The question is, how we can make this age of migration easier to live in and talk about? One of the environments in which this is a pertinent question is the museum, traditionally a place where objects are regarded as products of a specific, clearly demarcated culture. Until recently, collections were usually categorized according to ‘origin’ rather than ‘interchange’, more often valued as a canon of historical certainties than as bearers or witnesses of conflict and migration. Anthropologist Arjun Appadurai wondered a few years ago why objects in museum collections are not, like refugees, seen as ‘artefacts of excessive circulation’? Why are they not more often deployed to tell stories about their relocation? Can the stories of these ‘accidental refugees’ not contribute to a different concept of diaspora, of otherness, of ownership and of history? We would like to show perspectives that rise above historical boundaries and pay attention to the migration, transformation and use of objects.

It was a challenge indeed! The Röhsska Museum has an extremely diverse and rich collection, and it is hard to make a selection with a theme as elaborate as migration. We found inspiration in the above-mentioned text from Appadurai. Artist Fred Wilson, who in 1992 curated the exhibition Mining the Museum at the Maryland Historical Society in the USA, also inspired us. We liked the statement in which he addressed the biases of museums. In his installation, different objects ‒ art and artefact, high and low, dominant and marginal ‒ were carefully juxtaposed, thus prompting fresh readings and new iconographies, and assisting viewers in thinking critically about hidden meanings.

When we first visited the museum depot and scrolled through the collection (this was just before the lockdowns), we were immediately drawn to a couple of objects that stood out on account of their narrative qualities: the Syrian bottles from 200 BCE because of their iconic, unchanged form; the rich tapestries from the Middle Ages, acting as perfect image vehicles; the weavings made in the South African missionary crafts community Rorkes Drift, because they open up a great path into questioning cultural appropriation; the iron locks – linking the Swedish iron industry to a darker industry of slavery. Furthermore, we were intrigued by certain hypes and trends in collecting art and artefacts, for instance the craze that arose at the turn of the twentieth century with early renaissance chests.

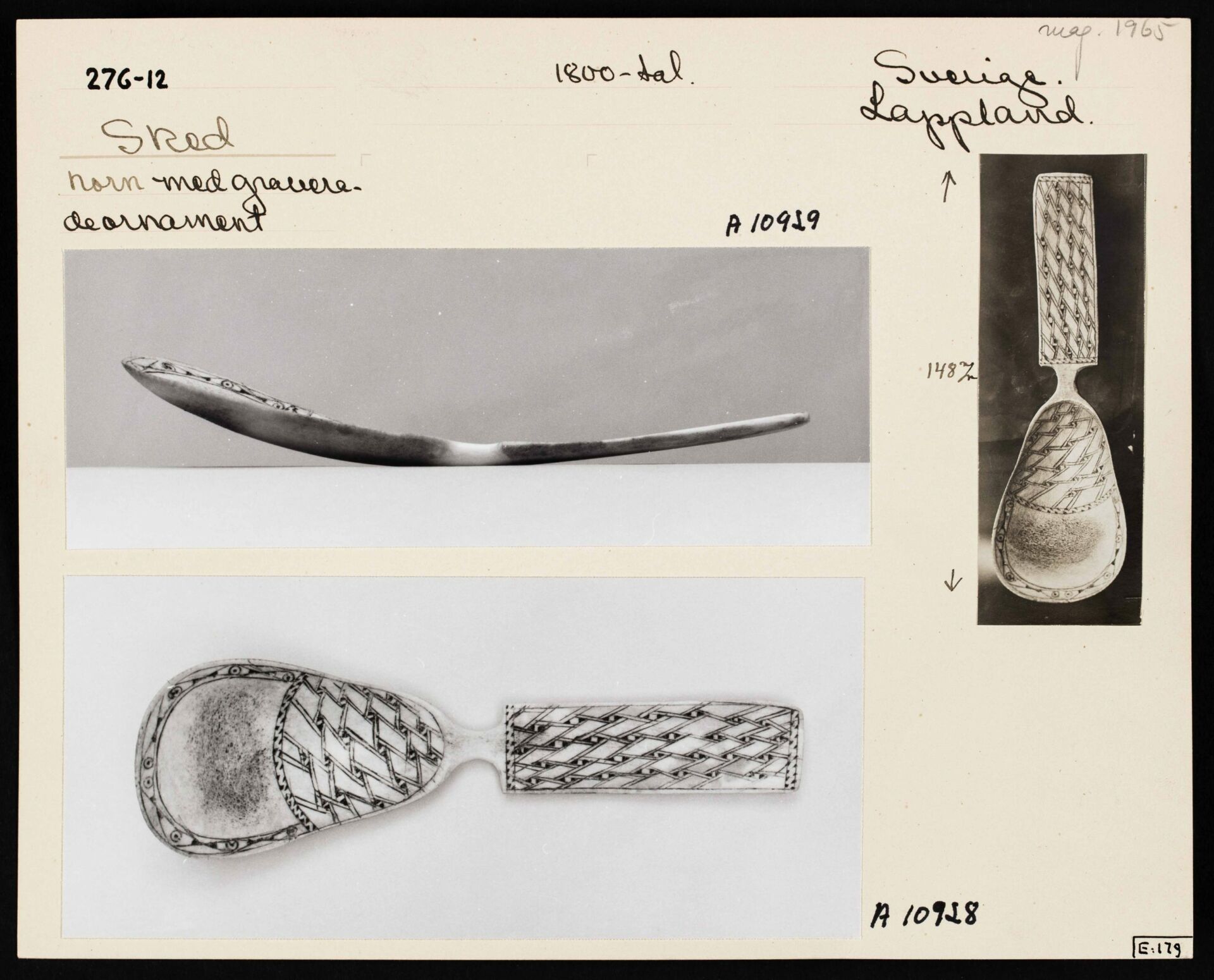

Catalogue card showing spoons carved from reindeer horn, nineteenth century, from the museum collection.

The catalogue index cards used by the museum from its foundation at the start of the twentieth century to the 1990s formed another inspiration. Like a ship’s logbook, the mostly handwritten cards reveal the materials, dimensions, origins and categorization of objects, as well as where and when they were collected. The catalogue cards of mediaeval chests and missionary tapestries underline once more how artefacts in museums have become separated from their makers and users. The index cards mirror the appropriation of things, as well as their ‘re-anchoring’ into classified objects. Migration aims to unfasten them and dig up their roots, routes and relationships.

Typologies, like the forged padlocks, the cast-iron tobacco caddies or the handcrafted Sami spoons, allow us to look at objects beyond their functional meaning. By arranging these objects in series you not only stress their similarities in form and function but also invite a closer inspection. Then you get to another layer, revealing the free interpretations within the ‘laws’ of each typology. It teaches us that objects can be part of a typological family but still have their own unique identity based on the personal decisions of the hand of the maker. Moreover these serial presentations enable you to understand how within certain typologies a form can evolve and patterns and motifs can migrate.

Print of exhibition catalog, photo: Carl Ander, Röhsska Museum.

The graphic identity for Migration is based on the representation of movement. The filmic use of typography, for instance, suggests words migrating across the page – each one heading in another direction. In photography, the concept of movement and motion is also present. Carl Ander has captured the objects being handled by the museum conservators, showing them in motion, as well as giving a rare glimpse behind the scenes of making this exhibition.

Top image: Ernst van der Hoeven & Kirsten Algera, MacGuffin Magazine. Photo: Carl Ander, Röhsska Museum.